|

Edgar Lucien Larkin |

Edgar

Lucien Larkin

By

Jake Brouwer

|

Edgar Lucien Larkin |

On this day, alone on the mountain in the shadow of the obelisk, and by night in under the ever-twinkling stars, a lone writer with laptop in hand will relish the tranquility of the mountain and the heavens as they merge nightly. Slowly an understanding will be put forth in words as it has been before on this mount. Perhaps this new volume of understanding and studies of the life and the Observatory will come forth and leave future generations remarking what a wonderful time this 1999 must have been to have moved one to write such a piece.

So it was 98 years ago on August 11, 1900 when Edgar Lucien Larkin found himself accepting the position of director of the Lowe Observatory. Larkin came to the Lowe Observatory on Echo Mountain from the Knox College Observatory in Galesburg Illinois. The California "fairyland" as he called it was to be his home for the next 25 years.

|

There on the mount was the Lowe Observatory in a vast amphitheater of colossal summits all round, some of equal heights to the observatory and others stretching some 1200 feet above. On it’s sides were the gaping canyons of Rubio and Las Flores. Often laid out before him was a heaping carpet of clouds stretching as far as the eye could see to the south, pierced on occasion by the peaks of Catalina Island. Then on clearer days can be seen the 900 square miles of patchwork plains of fruit and flower-laden plants that seem to be ever living green before him. In the East the dawn bursts from the clouds and the West, well sunsets such as these were worldly known. Looking to the waves of the Pacific Ocean Larkin would reminisce of the waves where he grew up in near Ottawa, Illinois. These were the waves of tall grass, which he often watched from a perch high in a tree.

Edgar Lucian Larkin was born in a log cabin along Indian Creek on April 5, 1847 to a father of ordinary means and a mother of high morality and nobility of mind. His parents were poor and Larkin himself said they could well be the topic for a writer of modern socialism with a title such as Submerged 9/10’s or Unequaled Distribution of Wealth. Try as they may Edgar’s parents sent him to the fields to plow corn and learn the ways of farming, but the weeds seemed to have escaped him altogether. Then he was put in sole charge of the cows, which Edgar took to and became great friends to them.

His grandfather built a frame house with pine boards brought to Ottawa on the new canal. When Edgar was eleven his father died and he and his mother went to live in the newly painted white frame house. Teachers were scarce commodities and books were the same. A retired German physician came into the area and had a library. Edgar read all the books the German had in English but the greatest of volumes were in German and like hieroglyphics to the young man.

In 1858 a school opened in the region and the task of teaching this future writer began. It was also in this same year that the greatest of events took place, which forever changed the course of life for Edgar Larkin. On October 5, 1958 Edgar lay asleep in bed when his grandmother awoke him and urged him to come outside and see the wonderful site. It was around 10:00 PM and the wonder site that awaited him was the Comet Donati. It appeared to be springing from their black forest and extended to the zenith. His eyes and those of many others had not before seen such a display.

The next day young Larkin at the age of 11 decided to study astronomy. With a dollar that would eliminate his Christmas present from grandmother that year, he bought his first book, Burrits Geography of the Heavens and Atlas. A nearby surveyor had a 4 inch lens which when placed in a piece of wood and an eyepiece added, became his first telescope to study with. By the time he was fourteen however his eyesight became so bad that he had to leave school and never returned.

In 1869 Larkin was married to Alice Anna Everman and a son was born. Within the next ten years Larkin built a private observatory in New Windsor, Illinois and on January 1, 1880 a 6 inch Clark equatorial with circles was set upon it’s pier. Larkin had the good fortune to meet Alvin Clark in his Cambridge, Massachusetts workshop. In this brief meeting Clark was working on a lens and Larkin was explained every particular about it as Clark went about his work. Little did Larkin realize then that he would be using that very lens one day in the Lowe observatory.

In the spring of 1888 he went to Knox College, placing all of his equipment in the newly constructed dome until he went to California.

Meanwhile in California Valentine Peyton current owner of the Mt. Lowe railway was being faced with the lesser of two problems to hit him that year. The first was the burning of the Echo Mt. House on February 5th 1900. The second was finding a replacement of the eighty year old Dr. Swift. Peyton bought the observatory equipment from Swift and was continuing to underwrite the operation but Dr. Swift who otherwise was in good health had begun to go blind. Larkin was selected to replace the aging director.

Edgar Larkin led Dr. Swift down the path from the observatory stopping at the first turn in the trail to look back. The observatory could be seen from base to top. Swift looked lovingly at his observatory. At the next turn only the dome could be seen but it seemed whiter than ever as the bright Californian sun was shining at it’s brightest illuminating the white hemispheres that covered the telescope. At the top of the Great Incline Dr. Swift took one last glance at the observatory with his pathetic eyes and then turned away to look no more, sinking into the depths of Rubio Canyon.

Later Larkin transferred Swift’s books to a large bookcase and unpacked his own from boxes recently shipped from Illinois and as he did so Professor Thaddeus Lowe made his way up to the observatory to meet the new director. After hellos and five minutes of ordinary talk things took an abrupt change and Larkin knew at once he was in the presence of a master mind. Larkin says, "I at once knew that I stood within a radiating sphere of pure intellect." Lowe knew the entire mechanism of the gigantic machine and the solar system. Lowe began to unfold his plans for a summit of scientific laboratories, institutions, and centers for higher learning that would enable any man to enjoy his pursuits and not lack for any of life’s amenities. The two immediately became friends.

|

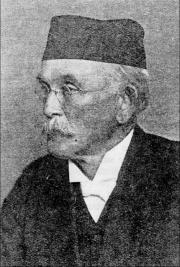

Spectroscopic instruments of the Lowe Observatory. |

Larkin showed Lowe his homemade heliostat for projection of light into a room and Lowe after witnessing the beauties that such a homemade instrument could make frowned with the disappointment that an observatory bearing his name could not afford a new heliostat. As it were in October of 1901 two elderly women, Jennie M. and Matilda H. Smith of Pittsburgh visited the Lowe Observatory. Upon seeing the sad state of the Larkins heliostat they promptly wrote a check for $120.00 to cover the cost of a new Brashear heliostat with glittering mirrors and a very accurate driving clock.

And so life for Larkin at the Lowe observatory began. By 1902 Pacific Electric had taken over the Lowe Observatory and realizing its importance promoted it in all of their literature. In a Lowe Observatory brochure the following was stated, "The Lowe Observatory is owned by the Pacific Electric Railway and for the free use of the public and is the only astronomical observatory in southern California open to visitors." Aside from his astronomical duties the director now became part of an informative and entertaining medium that was loved by all that visited the mountain observatory. Lectures by Larkin were free and on occasion George Wharton James would also lecture using a stereopticon. Rail cars we allowed to layover 45 minutes so patrons could hear the lectures on Saturday, Sunday and Holiday evenings. On other evenings the observatory and the services of the director were available to private parties and schools for which a special car could be arranged with the passenger department.

Larkin was not content simply doing his duties as director and giving glimpses of the heavens to the visiting tourists for on the dark quiet evenings was when he picked up his pen and wrote to the millions beyond the shadows of Mt. Lowe.

|

Larkin had started writing at the age of 22 for newspapers and magazines and his scrapbook shows 105 different publications that printed his works. It would take 18 to 20 volumes to reprint it if one took the time to cull out the best of them.

From February to August of 1902 his works were published in the San Francisco examiner. Edgar Lucien Larkin’s first book Radiant Energy published in 1904 was the gathering of all these works. It is dedicated to John D. Hooker who helped Larkin see the book through to press. This work of science shows his dedication to the subject in detail. In 1910 Larkin received some bad news. The storage building in which the plates, cuts and extra copies of his book Radiant Energy was destroyed. Unfortunately it was located next to the ill fated Los Angeles Times Building which was dynamited causing loss of life and property. Larkin had to bear the entire expense of his loss.

|

Delicate Spectroscope |

In 1904 the observatory and its director had guests of great distinction. William Pickering spent several months at the site using the 16-inch telescope to continue his studies of the moon and Jupiter’s satellites. Dr. George hale of the Yerkes observatory also came that year to find a suitable site for his 40 inch Snow telescope. Larkin opened his facilities to this guest but later a site on Mt. Wilson was picked.

On a windy night in December of 1905 Edgar Larkin made himself busy lashing down the 1 ½ ton dome on the observatory. Charles Lawrence, the Pacific Electric photographer, assisted Larkin packing away the delicate instruments against damage from the impending storm. Before long a gust of wind tossed the roof of the Casino building 60 feet to the east landing it atop of the Powerhouse and promptly a fire broke out which soon had the whole mountain ablaze. The 16-inch objective was lowered into the water tank for safety. The Lowe Observatory was the only surviving building on the mountain.

|

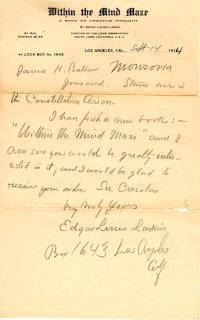

Within the Mind Maze personal stationary of Edgar Lucien Larkin signed by him and promoting his newest book |

During the years that followed Larkin wrote of his studies on Hindu, Egyptian, Greek Philosophies, esoteric mysteries and occult worlds in a book published in 1911 called Within the Mind Maze. It is a book for thinkers. It is for those who seek to know the universe by studying it from the physical side, the objective side, and that side apparent to our five senses.

In his solitude on these mountain heights Larkin had every opportunity for prolonged and profound thought. He dealt with themes that were considered appropriate for the annual meetings of learned societies and attended by men who are able to write half the alphabet after their names. He himself had such a list of societies he belonged to as is seen on the title pages of his books. And though he dealt with such vast and marvelous subjects he presented them to others with a charm and fascination that allured both the college man and the laborer.

And so it was many years ago that a man fascinated with he heavens, the mind, and the beauty around him, penned three books and hundreds of articles. Forever watching in the night sky seeing the edge of a Saturn ring as it cuts it way up and out of a rocky cliff, or a tiny Jupiter moon escaping from a tangle of Manzanita bushes far on the mountains top. The beauty of the skies blending with his surroundings did not escape him nor did the mysterious silence of that eerie place in the witching hours of the evening. For that was the time of greatest imagining. The time when no disturbing object was in sight and no harassing sound to be heard. At this hour and in the dense fog on the mountain silence solitude and stillness reign.

|

Edgar Lucien Larkin penned his last book in 1916, it was called the

Matchless Alter of the Soul and in 1925 he died suddenly leaving a most arduous task for

his son Ralph. His last wish was to have his ashes scattered across the summit of a peak

near Inspiration Point. This was a task that Ralph could not bear up to and asked the

assistance of Charles Lawrence. The peak sometimes referred to as Mt. Larkin came to be

the finally resting spot of the great man who found his home on Echo Mountain studying the

heavens and earth and all points in-between.

Send email to Echowebmaster@aaaim.com to report any problems.

Last modified: February 12, 1999

No part of this paper may be

reproduced in any form without written permission from:

Jake Brouwer

All articles and photos were provided by:

Land-Sea Discovery Group

Copyright © 1999