Rubio Canyon is a quiet and sacred place to me, rarely encountering others, I

can slip away into this magical canyon and drift back in time to relish in the revelry of

the railway’s heydays.

Rubio Canyon is a quiet and sacred place to me, rarely encountering others, I

can slip away into this magical canyon and drift back in time to relish in the revelry of

the railway’s heydays. Return to Echo Mtn. Echoes, Summer 1999 Cover

Remembering Rubio Canyon

By Jake Brouwer

On July 4, 1999, I thought to take a trek into Rubio Canyon. In part, for reverence to what has become a huge part of my "free" life, and in part to simply feel the memories that seem to ooze from every nook and cranny of the ancient canyon walls. Rubio Canyon is a quiet and sacred place to me, rarely encountering others, I

can slip away into this magical canyon and drift back in time to relish in the revelry of

the railway’s heydays.

Rubio Canyon is a quiet and sacred place to me, rarely encountering others, I

can slip away into this magical canyon and drift back in time to relish in the revelry of

the railway’s heydays.

Quietly passing by the block wall of the trailside home on Rubio Vista, it is mere seconds before I am in the wilds of Rubio Canyon. My worn boots kick up small puffs of dust as I walk the well deteriorated trail, and on occasion I stop to watch a lizard scramble across the trail from one tiny burst of brush to another. A canvas could not be more appropriately sketched, and painted, then the canvas that lies before me. The stark and glistening gray granite walls spiked with the verdure of yucca and Spanish Daggers are brought to an enlightening animation with the gentle and paper like orange petals of the California Poppies.

|

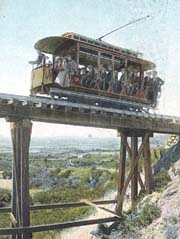

Shown here is

an early open observation car on one of the nine trestles leading into Rubio Canyon. (LSDG

Collection) |

Heading down the meandering trail I can somewhat detect the continuous clank, rattle, and clank of the passenger car as it works it way into the heart of the canyon across the tracks. Looking over the side to the canyon bottom teeming with oaks, sycamores, bays, and maples, I can all but experience the dizzying feeling of passengers peeking over the sides of the railcar, as the early narrow gauge car wound it’s way round the curves. Often it headed directly to the edge of the precipice, and then in the last possible moment darting around a bend to continue on it’s merry way.

Had the upper reaches of Lowe’s Scenic Mountain Railway not overshadowed Rubio Canyon, it would surely hold a much larger place in history, and in our minds. Rubio Canyon’s beginning’s hold other mysteries yet to uncover, from it’s local Gabrielino Indian lore, stories of marauding outlaws, water merchants, and let us not forget the man the canyon is named after, Jesus Rubio. For most of us though the real life of the canyon was first breathed when Thaddeus Lowe and David MacPherson celebrated the first blast of construction in 1891. MacPherson’s earlier survey in March of 1890 had displayed Rubio Canyon to be the best workable outset for the mountain railway.

|

A 1906

postmarked postcard of the Pavilion in Rubio Canyon. (LSDG Collection) |

At first, food, materials, and water were brought in my mule train. By September of 1892 track was laid all the way from Mountain Junction in Altadena, to the mouth of Rubio Canyon. Rails, ties and stringers were then loaded up on flatbed cars and hauled by horses to the end of the line, where piles of materials were stacked for the final, and what was to be the Herculean task of building the last mile of rail bed into the canyon.

Today, walking deeper into the canyon, the sheer walls of the West Side of the canyon become more confining. It was here that workmen were hung from rope to bore into the hard rock, place the powder, and then wait to be drawn back up before the explosion blasted the rock apart. Close inspection of the rock now reveals an occasional drill hole bored out more than one hundred years ago.

The trail I follow into Rubio Canyon skirts and dips into and around the little canyons, however in 1892 bridges traversed the way. Nine trestles crossed the expanses of the smaller canyons that fed into Rubio Canyon. The first was named Las Flores Bridge. This bridge was built of the same sized timbers used on the Santa Fe system’s bridges giving one a slightly more secure feeling as they crossed the depths below. These materials and the construction of this last mile placed a weighty burden on Thaddeus Lowe’s finances as the days went on.

|

The interior

of Rubio Pavilion's Dining Hall. |

Finally the workmen would place the poles and string the wire for the electrical system. In many areas the poles were set in the perpendicular solid rock walls. A Mr. S. H. Anderson made the first motorized trip back into the canyon on May 13th 1893. What a thrill it must have been for him to ride the gently rising electric trolley for the first time into the heart of the canyon. From that point on, construction took on a passion that was nearly unstoppable. The first passenger cars were neatly constructed using the flatbed construction cars, and adding benches and canopies.

|

Just up canyon

from the Rubio Pavilion these early sightseers pose in the woods alongside one of the

pipes which transported water from higher up in the canyon. (Courtesy Paul Rippens) |

At the same time work which began on Rubio Pavilion in February was now in full swing, and new rail line provided the materials to do construction on the Great Incline, MacPherson’s Trestle, and the Chalet up on Echo Mountain.

By the time the railway opened, the first of Thaddeus Lowe’s pleasure resorts was nearly finished. Rubio Pavilion was at an altitude of around two thousand feet, in itself, higher than that of many of the more popular resorts of the day located in the Catskill Mountains in New York. The dream was becoming a reality. Hotel Rubio and the Music Hall embellished this three level transfer point from the electric trolleys to the Great Incline. In the square tower of the simple wooden structure, the Professor held a room and office.

The hotel had a dozen rooms to accommodate guests ready by opening day, but nearly sixty bedrooms were planned. In the Music Hall, concerts, balls, parties and other entertainment were put on for the delight of the guests, as well as for private parties. Also provided were the ever-popular lectures of travel, often illustrated by the Magic Lantern show put on by such notables as the likes of George Wharton James, and John L. Stoddard. Below the platform the lower grip wheel for the Great Incline mechanism was placed, as well as various sized Pelton water wheels for power. There, also under the platform, much to the delight of many with appetite to whet, was a spacious thirty five by one hundred and ten-foot dining room. Finished in all natural dark woods by the Carson Brothers, the elegant dining room had not a post or pillar to obstruct views from anywhere in the room as it perched just above the canyon bottom. Said to be one of the largest dining and dancing halls in the country, Rubio Pavilion was indeed a place to be remembered even then. Off to the side was the kitchen, measuring seventeen by forty feet equipped with the most up to date conveniences.

|

This unusual

view on Rubio Pavilion's platform was taken in 1894. (LSDG Collection) |

The platform level of the Pavilion housed the ticket office, souvenir stand and served as the transfer point for passengers to disembark the electric trolleys and ready themselves for the hair-raising trip up the Incline. Here visitors got their first full glimpse of the Great Incline, and were present to witness the joy and delight of passengers returning from the heights above. Benches placed around various points of the platform provided ample opportunities for photographic recording of the memorable trip. This was also a popular layover spot for the conductors and workmen of the line.

And so one would think, "How can we possibly improve upon our visit here in Rubio Canyon?" A mere transfer point of beauty and ease for the sake of travel, or, how about the gateway to a fairyland of flora, rock formations, and trails leading to waterfalls of such unsurpassable beauty that one can simply close their eyes while there, and slip away into another dimension of time and space. For beyond the platform, the adventure of the first leg of the Scenic Mt. Lowe Railway continues on.

|

Lowe

addressing crowd at Suspended Boulder July 1, 1893 |

Where Thaddeus Lowe’s inspiration came from for this leg of the journey, can only be guessed upon. Perhaps his youthful days in the White Mountains of New Hampshire echoed a similar vision, which on seeing the wilds of Rubio Canyon, they evoked stimulus to create this wonderland so enjoyed by many.

From the very beginning the crowds came into Rubio Canyon. Picnic tables and benches were strategically placed about, and radiating from the backside of the pavilion, planked walkways and staircases led back deeper into the canyon to expose to all who cared to walk them, the beauties that therein lie. And, who could resist the temptation? This wild and almost frightening canyon of hewn porphyritic rock, rising hundreds of feet and its crags of surreal proportions, are somehow softened and made more inviting by the foliage of ferns, flowers, and vines trailing from the many trees and shrubs. The beauty of grassy nooks and moss-covered rocks are enhanced by the sparkling of the stream winding its way though the canyon, its spray at miniature cascades showers little diamonds on the tall grasses growing from the pebbly shores. It is along here that Lowe used thirty thousand feet of lumber to make the walkways and stairs that carefully guided visitors through the wonders of the canyon. Strung also were thousands of Chinese lanterns, which when lit at night, captivated all who were blessed enough to witness the affair. Whether an intermission between two caring couples in a lantern lit grotto, or an old mans tear shed at the simple beauty of the canyon, this is the romance of Rubio Canyon.

|

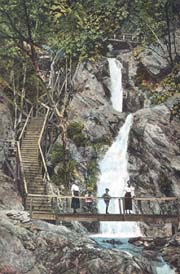

1000's of

steps led across and up around spectacular waterfalls in the upper reaches of Rubio

Canyon. |

Further on, the visitor is blessed to happen upon a thousand wooden steps crossing, and climbing deeper into the folds of the canyon, spanning chasms, and exposing to the viewer, the many falls discovered earlier on by those with adventure in their hearts. A dam built by Lowe for the storage of water for his power system in the 1890’s had a short life due to restrictions by the Rubio Land and Water Co. but until the recent events of this last year, this dam still stood in good condition.

At least nine waterfalls are revealed from one vantage point or another. Maidenhair Falls, Cavity Chute Falls, Bay Arbor Falls, Moss Grotto Falls, Grand Chasm Falls, Suspended Boulder Falls, Roaring Rift Falls, and Thalehaha Falls are the colorful names given to these cascades, varying in size from nine feet to one hundred ten feet. George Wharton James describes in his narrative of the MOUNT LOWE RAILWAY, the sight of a falls from the verandas of Echo Mountain House. "A delicately beautiful thread of water stealing down from a grove of rich green trees." This falls named Leontine Falls by H. A. Reid, is named after the wife of Professor Lowe, and is said to be the highest, and most beautiful of the entire Sierra Madre range. At this point I must caution the reader that the accessibility of all these falls is not as in days of old. This is a now very dangerous area not to be taken lightly.

|

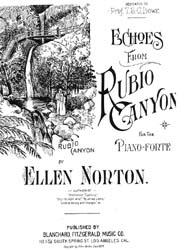

A rare

piece of sheet music titled "Echoes From Rubio Canyon" was published in 1894 and

dedicated to Prof. T.S.C. Lowe. |

Above a spot called Mirror Lake is Suspended Boulder. This spot recorded in historical works by Sharp, James, and others, is where Professor Thaddeus S. C. Lowe was captured on film as he addressed his guests on a preview tour of the area on Saturday, July 1, 1893. An elegant banquet at Hotel Rubio was a preamble to the tour.

A few days later on July 4, 1893 was the spectacular grand opening of the Mt. Lowe Railway. Hundreds of curious visitors packed the electric trolleys that brought them into the canyon wonderland. Many also rode their own buggies to the companies’ property at Cabrillo Heights at the mouth of Rubio Canyon, and rode a secondary car that took them the last distance to Rubio Pavilion. At the base of the Incline on the platform at Rubio, a throng of several thousand gathered to watch, as the first car, decorated in bunting, and topped by a glorious American flag, rose into the clouds carrying the Pasadena City Band.

|

An early

Newman Postcard view of Thalehaha Falls. |

During this time of national financial depression, people of Southern California, and the world, flocked to the grandest scenic mountain railway in the world. In the first four months it was estimated that over twenty thousand people visited, all passing through Rubio Canyon. The Mt. Lowe Railway had taken off like a skyrocket on the 4th of July appropriately enough.

Despite all this, Professor Lowe’s financial burdens finally forced a bankruptcy, which witnessed a few turnovers of the railway, and soon was in the hands of J. S. Torrance. Torrance installed a better power system on the Rubio Division, which led to the improved movement of people into, and out of the canyon. Torrance cleaned, cleared and improved the areas beyond the pavilion, making it an even more attractive and inexpensive place for family outings by the local residents.

|

A scene in Rubio

Canyon taken in the early 1990's by Jake Brouwer. |

In March of 1902, the railway was in the hands of Henry Huntington, and the Pacific Electric Railway. Huntington sought to increase visitation through reduced fare prices, a realization that took place after a considerable overhaul of the Rubio Canyon Division, which took almost five months. The narrow gauge line was replaced by standard gauge to hold the weight of the heavy double truck interurban Pacific Electric Cars that would carry more passengers. Curves were straightened, trestles removed and filled with earth and culverts, track replaced, and it would be nearly forty five days before the first of the new cars would run over the line into Rubio.

|

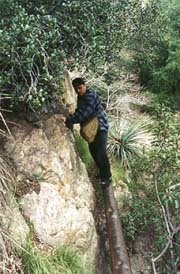

Jesse Perez

walks a water pipe above a short precipice. Hey! Look out for that Spanish Dagger! Photo

by Jake Brouwer 1998. |

At the same time the Rubio Hotel was closed to the public. Frequently floodwaters had caused damage to the underbelly of the pavilion, causing repetitive damage making it unsafe for the public. Moving into the Professors old room and office on the second floor in 1905, was Fred Drew, the newly appointed Rubio Canyon station agent. Drew and his family lived in Pasadena during the winter months, however in 1909 they moved back into the pavilion believing the winter threat was over. On February 12th of that year, just before lunch, an electrical storm caused a terrible disaster. Lightning bolts struck the wall of the canyon causing a horrendous avalanche of rock and rubble onto the tiered structure in its way. Drew’s two daughter’s Helen and Dorothy escaped by climbing into the waiting Incline car on the platform. Fred Drew was found pinned under rock, and in peril of drowning by Ernest Crocker a Pacific Electric employee. Crocker also found young George Drew with a concussion and broken hip. Under tons of debris the youngest of the clan, Thayer was found dead. Mrs. Drew was found unconscious, and badly injured. It was months before she and Fred were able to return home from their injuries.

After the wreckage was cleared away, Pacific Electric built a new structure to house the ticket office, souvenir stand, storage and other facilities, which stood until the last days of the railway. In 1938 another rainstorm caused massive flooding and destruction to the railway below the train shed. Tons of rubble tumbled into the Rubio Station itself, and by April 1, 1938, passenger service to the station was stopped forever.

In 1939 a permit was issued for the salvage of the structure, and by 1941 the structure and the rails were all gone.

So ends the saga of Rubio Canyon, or so one would think. Hikers and young explorers, forever given to travel the lesser-known paths of the mountains, remain to discover the remnants of Rubio and the wilds of its canyons. Some of those adventurers will speak, and have spoken of its glories, and passed its wonder on to others, some by word of mouth, and others in books.

Today, after walking among the rapidly eroding pillars that held the Rubio Pavilion, I walked the length of a water pipe, and in a childlike moment balanced thereon like Robin Hood in olden days, feeling like no wrong could do me in. I hopped and stepped from rock to rock, to a point in the streambed where I came upon, for the first time the destruction in the canyon. Knowing fully what to expect, as I was warned before hand, I still shed a tear and turned back for a lonely and empty walk to civilization. Please remember Rubio Canyon.

Return to Echo Mtn. Echoes,

Summer 1999 Cover

[ Issues | Search | Help | Subscribe | Comment | Websites ]

Send email to Echowebmaster@aaaim.com to report any problems.

Last modified: February 12, 1999

No part of this paper may be

reproduced in any form without written permission from:

Jake Brouwer

All articles and photos were provided by:

Land-Sea Discovery Group

Copyright © 1999